Second time lucky?

But the world has changed in the meantime, and in 2013 the same US antitrust regulator allowed Office Depot to acquire Officemax without divesting a single of the acquired business’s outlets. It did not take much time for Starboard Value, one of Staples very vocal shareholders, to notice the change of mood on the market and urge Staples to approach Office Depot again.

All seemed to be progressing as planned since the acquisition was announced on 2nd April of this year; the proposed deal was give a green light by the regulators in New Zealand on 5th June, followed by China one week later, and more recently Australia on 13th August. However, the US and European Union regulators have now decided to put that deal through close scrutiny. Almost six months after the initial announcement, Staples and Office Depot’s dream is suddenly at risk. So what is so different in North America and Europe compared to the eastern hemisphere?

All seemed to be progressing as planned since the acquisition was announced on 2nd April of this year; the proposed deal was give a green light by the regulators in New Zealand on 5th June, followed by China one week later, and more recently Australia on 13th August. However, the US and European Union regulators have now decided to put that deal through close scrutiny. Almost six months after the initial announcement, Staples and Office Depot’s dream is suddenly at risk. So what is so different in North America and Europe compared to the eastern hemisphere?

Same situation seen from two perspectives

The regulators in the United States and Canada are understandably concerned that from three major office supply chains in 2013, the market effectively would only have one such chain form 2016 onwards. Whilst Staples and Office Depot have each broadened their product ranges well beyond traditional stationery items, equipment and office furniture, to include also a range of associated services, the coming together of Staples and Office Depot gives a new meaning to “one stop shop” if there is no other shop to go to!

The regulators in the United States and Canada are understandably concerned that from three major office supply chains in 2013, the market effectively would only have one such chain form 2016 onwards. Whilst Staples and Office Depot have each broadened their product ranges well beyond traditional stationery items, equipment and office furniture, to include also a range of associated services, the coming together of Staples and Office Depot gives a new meaning to “one stop shop” if there is no other shop to go to!

“We expect to recognize at least $1 billion of synergies as we aggressively reduce global expenses and optimize our retail footprint. These savings will dramatically accelerate our strategic reinvention which is focused on driving growth in our delivery businesses and in categories beyond office supplies.” says Staples’ Chairman and CEO Ron Sargeant. That broadening into new categories will result in Staples and Office Depot being confronted with new competitors as they enter these new categories, some of them with regional strongholds or a specific focus that can allow them to co-exist profitably side-by-side with the newly created monolith. Compared to the situation that prevailed in 1997 when Staples and Office Depot’s first attempt to merge was aborted, the key difference is the emergence and explosive growth of on-line retail, which has allowed many new entrants to carve out their slice of the market.

Language and geographical barriers in Europe have not allowed on-line retail to grow at the same pace as in North America, which is why the European Union regulator is of the opinion, until further proof that might emerge from the current investigation, that the proposed Staples and Office Depot merger will have a more detrimental impact on competition in mainland Europe that it might have in North America.

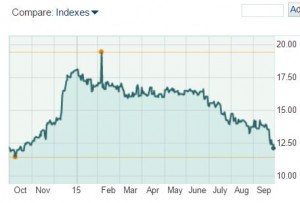

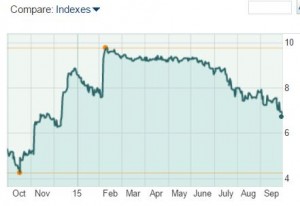

So the jury is out. The European Union will announce its decision by 10th February 2016. This is somewhat of a blow to Staples and Office Depot who had planned on completing their deal before the end of the current year (and are still pushing hard to do so). Evidently, after the jubilation of February, the uncertainty around the final outcome of this very bold bid is having its toll on the share price of both companies.

One may still hope that the European regulator will deliver a verdict before the full 90 days to which they are entitled to carry out their detailed investigation, but civil servants do not receive a bonus for productivity, so things may well drag on until 10th February 2016. I have indeed worked on some acquisitions that were given the green light at the close of business on the very last day of the regulator’s deadline, putting everyone through a nail-biting suspense…

The benefit of Office Depot’s expertise

The deal, which is all too often referred to as a merger between Staples and Office Depot, is clearly an acquisition, and although both parties have alluded to integrating in the spirit of a merger, Staples have already unequivocally stated that the headquarters of the combined company will remain in Framingham MA. So there could well be some office space for rent in Boca Raton FL, if the deal goes ahead. Nonetheless, Office Depot’s Chairman and CEO Roland Smith sees the proposed deal as “an endorsement … of the success [Office Depot] has had integrating OfficeMax over the past year”.

That experience may definitely come well in hand if Staples and Office Depot are allowed to proceed with their dream, because in spite of the high percentage of post M&A integrations that fail, companies that have repeated or at least recent experience of post-M&A integration become better at it as they repeat that experience, avoiding the multiple traps and pitfalls into which the majority of the first-timers tend to fall.

That experience may definitely come well in hand if Staples and Office Depot are allowed to proceed with their dream, because in spite of the high percentage of post M&A integrations that fail, companies that have repeated or at least recent experience of post-M&A integration become better at it as they repeat that experience, avoiding the multiple traps and pitfalls into which the majority of the first-timers tend to fall.

Integrating Staples and Office Depot will be a programme of far greater magnitude than Office Depot’s recent integration of OfficeMax, however that experience will provide a reality check in terms of resource requirements, time-lines, benefits realisation and integration methodology. For that to happen, the two companies will indeed need to integrate “in the spirit of a merger”, because the acquirer will need to learn from the acquired company.

So unless the regulators ruin the whole show, this one has the potential to be a very successful integration indeed. Let’s wish Staples and Office Depot good luck!

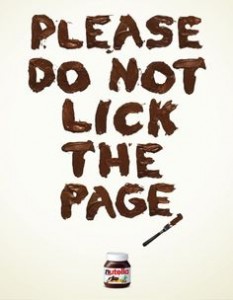

Both Thornton and Ferrero began as little corner shops; their history is closely associated with their founding families. But that is probably where the comparison stops. Whereas Ferrero developed over the years into a formidable marketing machine, a game changer in the chocolate industry, Thornton remained anchored in tradition. Oddly, it is that traditional image that appears to have attracted Ferrero; the remaining question being whether Ferrero will manage to brush away the “dusty” and “passé” aspects of that tradition, and fully exploit the concept of “authenticity” that underlies tradition. Given their strong track-record as powerful communicators, transforming the image of Thornton’s is probably not beyond Ferrero’s reach, but it will be quite a task…

Both Thornton and Ferrero began as little corner shops; their history is closely associated with their founding families. But that is probably where the comparison stops. Whereas Ferrero developed over the years into a formidable marketing machine, a game changer in the chocolate industry, Thornton remained anchored in tradition. Oddly, it is that traditional image that appears to have attracted Ferrero; the remaining question being whether Ferrero will manage to brush away the “dusty” and “passé” aspects of that tradition, and fully exploit the concept of “authenticity” that underlies tradition. Given their strong track-record as powerful communicators, transforming the image of Thornton’s is probably not beyond Ferrero’s reach, but it will be quite a task…

As a privately owned company, Ferrero does not need to disclose its strategy to the world, and nobody at this stage can be certain of what is going through Giovanni Ferrero’s mind. Does he really intend to revive the Thornton brand? Can the Thornton retail outlets be used as a channel for a premium Ferrero/Thornton range whilst Nutella, Ferrero Rocher and Kinder® products continue to flow through high-street shops and retail chains? How important are the Derbyshire factory and the know-how of some of its staff to Ferrero’s global manufacturing foot-print?

As a privately owned company, Ferrero does not need to disclose its strategy to the world, and nobody at this stage can be certain of what is going through Giovanni Ferrero’s mind. Does he really intend to revive the Thornton brand? Can the Thornton retail outlets be used as a channel for a premium Ferrero/Thornton range whilst Nutella, Ferrero Rocher and Kinder® products continue to flow through high-street shops and retail chains? How important are the Derbyshire factory and the know-how of some of its staff to Ferrero’s global manufacturing foot-print?

The union of FedEx and TNT is clearly positioned to break into Europe’s top league and preventing DHL and UPS from achieving total hegemony in that region. Perversely, for UPS that threat could also be a pivotal opportunity; UPS have not had an easy time in Europe in recent years but the strategy they appear to be following is consistent and may bear some fruit. Recently, a UPS spokesman stated that his company is constantly evaluating the marketplace for potential acquisitions and that it would be investing more than $1 billion to expand its European business organically. Recent acquisitions, such as Kiala in 2012, which increased UPS’s reach at package pickup points at kiosks and other small stores, are proof that UPS’s expansion strategy is being implemented.

The union of FedEx and TNT is clearly positioned to break into Europe’s top league and preventing DHL and UPS from achieving total hegemony in that region. Perversely, for UPS that threat could also be a pivotal opportunity; UPS have not had an easy time in Europe in recent years but the strategy they appear to be following is consistent and may bear some fruit. Recently, a UPS spokesman stated that his company is constantly evaluating the marketplace for potential acquisitions and that it would be investing more than $1 billion to expand its European business organically. Recent acquisitions, such as Kiala in 2012, which increased UPS’s reach at package pickup points at kiosks and other small stores, are proof that UPS’s expansion strategy is being implemented.

Alcatel-Lucent, like most of the major telecommunication equipment providers, is today the result of a number of acquisitions and business integrations. Alcatel and Lucent’s merger in 2006 triggered the merger of Nokia Networks with Germany’s Siemens. As an after-shock five years later, Ericsson acquired Nortel’s wireless networking business, prompting Nokia to buy out Motorola’s infrastructure division…

Alcatel-Lucent, like most of the major telecommunication equipment providers, is today the result of a number of acquisitions and business integrations. Alcatel and Lucent’s merger in 2006 triggered the merger of Nokia Networks with Germany’s Siemens. As an after-shock five years later, Ericsson acquired Nortel’s wireless networking business, prompting Nokia to buy out Motorola’s infrastructure division…