Energy and persistence conquer all things (Benjamin Franklin)

After four unsuccessful bids, it is befitting that the deadline set by the U.K.’s Takeover Panel for beer giant Anheuser-Busch InBev NV to submit a fifth and final offer for SABMiller Plc. was extended to 5 p.m. GMT on 11th November : Armistice Day !

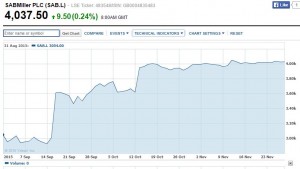

Rumours that AB InBev were about to bid for SABMiller started over twelve months ago, gaining substance shortly afterwards. What ensued was a succession of bids of ever increasing value to seduce the initially reluctant shareholders of SABMiller – until they surrendered to a staggering offer of USD 107 billion, or £ 71 billion. They can hardly be blamed for grabbing the cash and running, given that SABMiller’s share price at the end of November stands 37% higher than it was on 14th September, as a direct result of AB InBev’s mounting bids. Whilst SABMiller’s share owners might drink to celebrate having realised value growth earlier than expected, many other stakeholders are guaranteed a nasty hangover as a result of the forthcoming merger.

Rumours that AB InBev were about to bid for SABMiller started over twelve months ago, gaining substance shortly afterwards. What ensued was a succession of bids of ever increasing value to seduce the initially reluctant shareholders of SABMiller – until they surrendered to a staggering offer of USD 107 billion, or £ 71 billion. They can hardly be blamed for grabbing the cash and running, given that SABMiller’s share price at the end of November stands 37% higher than it was on 14th September, as a direct result of AB InBev’s mounting bids. Whilst SABMiller’s share owners might drink to celebrate having realised value growth earlier than expected, many other stakeholders are guaranteed a nasty hangover as a result of the forthcoming merger.

The combined business is set to rake in annual revenues of USD 73 billion, which is more than companies such as Pepsico or even Google. But more importantly, the integration of the two companies aims to generate annual cost synergies of USD 1.4 billion, a significant part of which will come from headcount cuts. With AB InBev employing 155,000 people worldwide, and SABMiller a further 70,000, it is easy to imagine how much duplication there will be at headquarter level as well as in many back-office functions. Having paid 15% more to acquire SABMiller than their initial bid of £ 38 per share, there is no doubt the pressure to realise the cost synergies very fast will be extreme.

A foreseeable domino effect on the beer market

Beyond the USD 1.4 annual savings, much of the business case underlying the acquisition of SABMiller rests on growth in Africa and Latin America. This is because AB InBev cannot expect much growth in Europe and North America where consumers are beginning to seek product differentiation and thereby generating growth at the other end of the beer market spectrum : micro-breweries or so-called “craft brewers”.

Beyond the USD 1.4 annual savings, much of the business case underlying the acquisition of SABMiller rests on growth in Africa and Latin America. This is because AB InBev cannot expect much growth in Europe and North America where consumers are beginning to seek product differentiation and thereby generating growth at the other end of the beer market spectrum : micro-breweries or so-called “craft brewers”.

Nonetheless, the combined companies’ market share in North America and the fact that AB InBev own wholesale distributors in several states of the USA might be sufficient to restrain the route to market of many smaller players and this may reduce consumer choice in bars and retail outlets; so this could be bad news for those who have thus far developed well by offering consumers something that differs from the usual mass product.

Global market share of five biggest beer companiesAnheuser-Busch InBev – 20.8%SABMiller – 9.7%Heineken – 9.1%Carlsberg – 6.1%China Resources Enterprise – 6%Source: Euromonitor, based on 2014 figures |

In spite of SABMiller selling its stake in a venture with Molson Coors for USD 12 billion and thereby letting go of the Coors and Miller brands, the combined AB InBev and SABMiller will be selling one in every three pints of beer worldwide, leaving a huge market share gap between themselves and the next player on the podium. Heineken and Carlsberg must now be furiously re-thinking their strategies; a number of other takeovers and mergers will inevitably happen as the industry seeks a new equilibrium.

According to Bart Watson, chief economist at the Brewers Association, there are already rumours about a Heineken and Molson Coors tie-up as these two companies are now seeing their main competitor become even bigger. Others are likely to follow. Some companies such as Diageo, which is now focusing on its spirits business, could stand to benefit from this new wave of upheaval on the beer market by finding an acquirer prepared to pay over the odds for Guinness as the few remaining global players grapple to keep pace with AB InBev / SABMiller. Interesting times ahead…

Africa : two different interpretations of public health

My thoughts regarding the impact this merger will have on consumer choice have not changed since the blog I published in September 2014 (“Something big could be brewing”), but one new aspect which is now surfacing is the very strong opposition and criticism of the merger which is now emanating from public health circles regarding the African continent, which is a critical growth area in the combined company’s strategy. According to Dr Jeff Collin, director of the Global Public Health Unit at the University of Edinburgh, the AB InBev SABMiller merger aims to “exploit Africa’s low per capita consumption of beer” by targeting low income consumers to generate sales growth.

In an article published in the British Medical Journal, a team of experts warn of “disturbing implications” relating to the growing alcohol related harm being witnessed in low and middle income countries. And therefore the issue is not specifically African, but also affects other regions targeted in the combined company’s growth plans, notably Latin America and China, the latter being the world’s largest beer market in which SABMiller has a joint-venture producing the country’s Nr 1 beer brand, Snow.

In an article published in the British Medical Journal, a team of experts warn of “disturbing implications” relating to the growing alcohol related harm being witnessed in low and middle income countries. And therefore the issue is not specifically African, but also affects other regions targeted in the combined company’s growth plans, notably Latin America and China, the latter being the world’s largest beer market in which SABMiller has a joint-venture producing the country’s Nr 1 beer brand, Snow.

Unsurprisingly, SABMiller see things very differently, stating that more than half of the alcohol consumed on the African continent is what they call “informal”, in other words beverages produced in unregulated facilities, ranging from home made beer brewed in a back yard to dubious distilled beverages containing potentially dangerous by-products such as methylated spirits, reminiscent of the Moonshine that was distilled during the Prohibition in the USA. Based on that premise, SABMiller see their mission as a noble task; as per their spokesperson: “The backbone of SABMiller’s growth strategy in Africa is to ensure the affordability of our beers so that local, low income consumers move from drinking poor quality, and potentially lethal, alcohol to enjoying our high quality beers made with local ingredients.”

Many people will consider that strategy to be a little cynical; but there is one undoubtedly positive element in that statement: “local ingredients”. In the beer industry, the supply chain costs can be a substantial component of the value chain because of the unfavourable weight/volume to value ratio. Consequently, unlike wine and distilled beverages, there is a strong incentive for beer to be produced locally. And that, for emerging economies, is better than burdening the balance of trade with the cost of imported drinks.

Money now vs. safeguarding against a possible longer term threat

As in the more developed economies, low and middle income economies will see a growing tension between the priorities of their public health programmes and the fiscal requirements of their treasury; migrating the production of beer from back yards and speak-easy environments to a registered and regulated business is a source of corporation tax and possibly some form of alcohol tax as well. This also promotes employment in hygiene conscious factories, which is also important in developing economies.

As in the more developed economies, low and middle income economies will see a growing tension between the priorities of their public health programmes and the fiscal requirements of their treasury; migrating the production of beer from back yards and speak-easy environments to a registered and regulated business is a source of corporation tax and possibly some form of alcohol tax as well. This also promotes employment in hygiene conscious factories, which is also important in developing economies.

The authors of the article in the British Medical Journal argue that company’s proposed expansion in low and middle income countries “echoes that of transnational tobacco companies” whilst benefiting from less stringent regulation and controls. That might be the case, but faced with the dilemma of choosing between the certainty of a stream of income and the longer term avoidance of a possible health risk, I will not be surprised if the said low and middle income economies will welcome the growth of AB InBev/SABMiller in their respective countries.

Even in the absence of strong political opposition to the merging of the world’s two largest players, implementing the integration of these huge businesses will be a monumental task. Let’s wish them luck (and perseverance), and hope this will not end up with a big hang-over for all those involved. If it does, maybe the other mega-merger which is currently under discussion, namely the USD 160 billion bid by Pfizer to acquire Allegan, will be able to provide the cure to that hang-over!

Both Thornton and Ferrero began as little corner shops; their history is closely associated with their founding families. But that is probably where the comparison stops. Whereas Ferrero developed over the years into a formidable marketing machine, a game changer in the chocolate industry, Thornton remained anchored in tradition. Oddly, it is that traditional image that appears to have attracted Ferrero; the remaining question being whether Ferrero will manage to brush away the “dusty” and “passé” aspects of that tradition, and fully exploit the concept of “authenticity” that underlies tradition. Given their strong track-record as powerful communicators, transforming the image of Thornton’s is probably not beyond Ferrero’s reach, but it will be quite a task…

Both Thornton and Ferrero began as little corner shops; their history is closely associated with their founding families. But that is probably where the comparison stops. Whereas Ferrero developed over the years into a formidable marketing machine, a game changer in the chocolate industry, Thornton remained anchored in tradition. Oddly, it is that traditional image that appears to have attracted Ferrero; the remaining question being whether Ferrero will manage to brush away the “dusty” and “passé” aspects of that tradition, and fully exploit the concept of “authenticity” that underlies tradition. Given their strong track-record as powerful communicators, transforming the image of Thornton’s is probably not beyond Ferrero’s reach, but it will be quite a task…

As a privately owned company, Ferrero does not need to disclose its strategy to the world, and nobody at this stage can be certain of what is going through Giovanni Ferrero’s mind. Does he really intend to revive the Thornton brand? Can the Thornton retail outlets be used as a channel for a premium Ferrero/Thornton range whilst Nutella, Ferrero Rocher and Kinder® products continue to flow through high-street shops and retail chains? How important are the Derbyshire factory and the know-how of some of its staff to Ferrero’s global manufacturing foot-print?

As a privately owned company, Ferrero does not need to disclose its strategy to the world, and nobody at this stage can be certain of what is going through Giovanni Ferrero’s mind. Does he really intend to revive the Thornton brand? Can the Thornton retail outlets be used as a channel for a premium Ferrero/Thornton range whilst Nutella, Ferrero Rocher and Kinder® products continue to flow through high-street shops and retail chains? How important are the Derbyshire factory and the know-how of some of its staff to Ferrero’s global manufacturing foot-print?

Cement is bulky, heavy and of low value relative to its weight. The market catchment area for any given production plant is therefore quite limited as transport costs rapidly outweigh economies of scale. The positive side of this is that cement is one sector in which mature economies are not likely to be invaded by Chinese production, even if China now accounts for more than half of the world’s cement consumption. A producer’s geographical spread is therefore a key factor. In that sense, Holcim and Lafarge complement each other particularly well in the fast growing economies, as the former is strong in Latin America and Asia whilst the latter is well positioned in Africa and the Middle East. The pair believe that the lower risk and business fluctuations resulting from better geographical spread will reduce their borrowing costs, thereby generating annual savings of some 200 million Euros.

Cement is bulky, heavy and of low value relative to its weight. The market catchment area for any given production plant is therefore quite limited as transport costs rapidly outweigh economies of scale. The positive side of this is that cement is one sector in which mature economies are not likely to be invaded by Chinese production, even if China now accounts for more than half of the world’s cement consumption. A producer’s geographical spread is therefore a key factor. In that sense, Holcim and Lafarge complement each other particularly well in the fast growing economies, as the former is strong in Latin America and Asia whilst the latter is well positioned in Africa and the Middle East. The pair believe that the lower risk and business fluctuations resulting from better geographical spread will reduce their borrowing costs, thereby generating annual savings of some 200 million Euros. Conceptually and intellectually, this is quite an appealing and exciting challenge, but it is difficult to imagine such transformation within the next three to five years in two companies which until now have relied mostly on size and hegemony (and some times price-fixing when the going became too tough) rather than being agile and capable of re-inventing themselves by adding a service veneer over their heavy industry core.

Conceptually and intellectually, this is quite an appealing and exciting challenge, but it is difficult to imagine such transformation within the next three to five years in two companies which until now have relied mostly on size and hegemony (and some times price-fixing when the going became too tough) rather than being agile and capable of re-inventing themselves by adding a service veneer over their heavy industry core.