A bitter saga

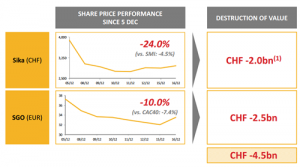

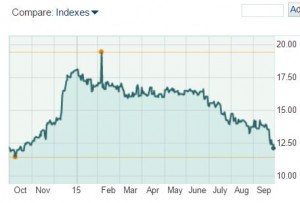

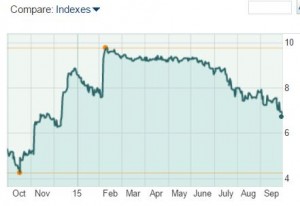

Whatever the outcome of the challenged take-over of Sika by Saint-Gobain, which was first announced in December 2014, there will be bitter lessons to be remembered in the future, and other companies whose capital structure includes shares with preferential voting rights might see their value plunge unless they can provide the clarity that is so obviously missing in the case of Sika.

When a minority shareholder holds the majority of the voting rights, that shareholder can unilaterally make decisions that serve self-interest but are seriously detrimental to the interests of the shareholder majority – and this is what is happening at Sika, whose founding family’s holding company owns 16% of the shares but 52% of the voting rights, allowing them de facto to do whatever they please.

An inevitable conflict of interest

Saint-Gobain are offering a 78% premium for the stake of the Burkard family and it is easy to understand why that family is eager to accept the USD 2.9 billion they are being offered. However, Saint-Gobain have no intention of making an offer on the rest of Sika’s capital; why acquire any more when their proposed acquisition of 16% of the capital will suffice to give them full control of the company. It is hardly any wonder that the proposed transaction caused an immediate outcry from the remaining shareholders who claim that the deal should not be allowed to proceed unless a public offering is made for the remainder of the share capital.

Saint-Gobain and Sika are today direct competitors. If the deal goes ahead, Saint-Gobain will only reap 16% of Sika’s future profits, therefore the synergies and any other benefits resulting from the acquisition will be biased to benefit Saint-Gobain far more than Sika, thereby weakening Sika and further undermining the value of the other shareholders’ investment. These other shareholders include the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation whose high profile has given the Saint-Gobain Sika deal worldwide exposure. The Gates trust released a statement declaring that “the proposed transaction makes no strategic sense, is an affront to good corporate governance and is not in the interest of Sika’s business, employees, customers or public bearer shareholders”. It is obvious from that statement that the Gates trust will fight tooth and nail to block the proposed sale. This is war.

The narrow interpretation of the law

Just like many other Swiss companies, and indeed companies across Europe, Sika’s articles of association contain a number of oddities, in this particular case an “opt out” clause which stipulates that a sale of 33.33% of the company’s voting rights can be made without an open public offer to bid for the rest of the capital. As the Gates trust rightly states, this clause flies in the face of good corporate governance, but the Swiss federal administrative court confirmed on 1st September the opinion voiced earlier by Switzerland’s M&A Commission (COPA, Commission Suisse des OPA) that Sika’s opt-out clause is legal under Swiss law, according to which opt-out clauses must be challenged within 2 months of being introduced, after which they are binding. The only possibility of removing such a clause after that deadline is to modify the company’s articles of association, which requires a majority vote by the shareholders; quite a challenge when 52% of the votes are in the hands of the Burkard family who argue that investors in the company should have been aware of Sika’s share structure.

Nonetheless, whilst the COPA declared the opt-out clause to be legal, it did not attempt to clarify whether this particular instance the opt-out clause was being invoked in an abusive way.

New creative tactics and a criss-cross of legal challenges

With the opt-out clause confirmed as legal under Swiss law, but in theory still open to challenge as to whether it was being invoked in an abusive manner in this particular instance, the remaining shareholders sought other ways of proving that the Burkard family was serving its own interests to the detriment of the other shareholders and the company as a whole. This was prompted by the Swiss trust fund ETHOS which requested at a shareholders’ meeting that the controversial opt-out clause be removed; the objective of that request was to prove that by opposing ETHOS’ proposal, the Burkard family was voting in self-interest and more importantly against the interest of the majority of shareholders.

To add to the confusion, it was unclear whether the special shares to be sold by the Burkard family were subject to the restriction requiring sales of more than 5% of the capital to be approved by the Board of Directors. And in an separate further legal case, as the majority of the Directors are opposed to the transaction, the Burkard family is arguing they were prevented from using their full 52% voting rights to elect new Board Director and remove some of those in place.

In an additional layer of legal complexity, the Bill and Belinda Gates Foundation is now attempting to sue Urs Burkard, who represents the family and is the only member of that family on the Sika Board of Directors, for failing to act in the company’s best interest when he negotiated the sale of his family’s shareholding to Saint-Gobain. Legal claims against specific members of a Board have a weaker legal basis in Switzerland than they would in the United States, and Urs Burkard’s spokesperson has so far dismissed the threat of such legal action.

In an additional layer of legal complexity, the Bill and Belinda Gates Foundation is now attempting to sue Urs Burkard, who represents the family and is the only member of that family on the Sika Board of Directors, for failing to act in the company’s best interest when he negotiated the sale of his family’s shareholding to Saint-Gobain. Legal claims against specific members of a Board have a weaker legal basis in Switzerland than they would in the United States, and Urs Burkard’s spokesperson has so far dismissed the threat of such legal action.

So far, the only actors in this dramatic saga to benefit from the current criss-cross of recriminations and court cases have been the lawyers.

The final legal verdict vs. company reputation

On 15th September, the Swiss Competition Commission (COMCO) had little other choice than to unconditionally authorise the acquisition by Saint-Gobain of control over Sika, given the favourable ruling on that matter by the European Commission in July and the decisions made earlier by other competition regulators, particularly in China and in the USA.

On 15th September, the Swiss Competition Commission (COMCO) had little other choice than to unconditionally authorise the acquisition by Saint-Gobain of control over Sika, given the favourable ruling on that matter by the European Commission in July and the decisions made earlier by other competition regulators, particularly in China and in the USA.

Done deal? Not yet, mainly because of the on-going legal proceedings, but also because Sika’s directors and shareholders will continue to obstruct this acquisition by every possible means. Initially, the deadline for closing the deal was set to year end of 2015, but that had to be extended to mid-2016. A lot can still happen until then.

Ultimately, what might block the deal is the threat to the reputation of Saint-Gobain’s, whose share capital is largely in the hands of institutional investors who will not be impressed by Saint-Gobain’s contempt for shareholders. If the deal goes ahead, Sika’s shareholders will forego the opportunity to benefit from the 78% premium being offered to the Burkard family, and face the prospect of future decline of their shares’ value. If the Bill and Belinda Foundation, whose backing of worthwhile causes is acclaimed the world over, is hit financially by the Sika Saint-Gobain transaction, Saint-Gobain may be faced with a well deserve torrent of negative PR.

Ultimately, what might block the deal is the threat to the reputation of Saint-Gobain’s, whose share capital is largely in the hands of institutional investors who will not be impressed by Saint-Gobain’s contempt for shareholders. If the deal goes ahead, Sika’s shareholders will forego the opportunity to benefit from the 78% premium being offered to the Burkard family, and face the prospect of future decline of their shares’ value. If the Bill and Belinda Foundation, whose backing of worthwhile causes is acclaimed the world over, is hit financially by the Sika Saint-Gobain transaction, Saint-Gobain may be faced with a well deserve torrent of negative PR.

Can a company hide behind legal court decisions to act unethically? In theory the answer appears sadly to be yes, but if they do they will have to accept the consequences.

Food for thought …

The regulators in the United States and Canada are understandably concerned that from three major office supply chains in 2013, the market effectively would only have one such chain form 2016 onwards. Whilst Staples and Office Depot have each broadened their product ranges well beyond traditional stationery items, equipment and office furniture, to include also a range of associated services, the coming together of Staples and Office Depot gives a new meaning to “one stop shop” if there is no other shop to go to!

The regulators in the United States and Canada are understandably concerned that from three major office supply chains in 2013, the market effectively would only have one such chain form 2016 onwards. Whilst Staples and Office Depot have each broadened their product ranges well beyond traditional stationery items, equipment and office furniture, to include also a range of associated services, the coming together of Staples and Office Depot gives a new meaning to “one stop shop” if there is no other shop to go to!

That experience may definitely come well in hand if Staples and Office Depot are allowed to proceed with their dream, because in spite of the high percentage of post M&A integrations that fail, companies that have repeated or at least recent experience of post-M&A integration become better at it as they repeat that experience, avoiding the multiple traps and pitfalls into which the majority of the first-timers tend to fall.

That experience may definitely come well in hand if Staples and Office Depot are allowed to proceed with their dream, because in spite of the high percentage of post M&A integrations that fail, companies that have repeated or at least recent experience of post-M&A integration become better at it as they repeat that experience, avoiding the multiple traps and pitfalls into which the majority of the first-timers tend to fall.

The whole notion of market dominance is entirely dependent on how the market is defined. The commission’s panel has concluded that “customers would not face a reduction in choice, value or lower-quality service as a result of the merger“. A reduction in choice between what and what? After the merger, Britain will be left with only one major single-priced retailer, hence the CMA’s initial apprehension, but is that the environment within which consumers make their choice?

The whole notion of market dominance is entirely dependent on how the market is defined. The commission’s panel has concluded that “customers would not face a reduction in choice, value or lower-quality service as a result of the merger“. A reduction in choice between what and what? After the merger, Britain will be left with only one major single-priced retailer, hence the CMA’s initial apprehension, but is that the environment within which consumers make their choice?

Possibly the best way to understand the regulators’ thinking is to view “choice” as a moderator of pricing. If consumers view Scotch whisky as a more prestigious category than, say, Thai or Indian whisky, then owning a significant share of total Scotch whisky premium products can offer the potential to influence pricing upwards to fully capitalize on that favourable image, and even lead the way for lesser competitors within the segment to follow suit, in the absence of the pressure that would otherwise occur in a more fragmented market.

Possibly the best way to understand the regulators’ thinking is to view “choice” as a moderator of pricing. If consumers view Scotch whisky as a more prestigious category than, say, Thai or Indian whisky, then owning a significant share of total Scotch whisky premium products can offer the potential to influence pricing upwards to fully capitalize on that favourable image, and even lead the way for lesser competitors within the segment to follow suit, in the absence of the pressure that would otherwise occur in a more fragmented market.

Just over a decade ago, uniting Holcim and Lafarge would have been unthinkable. Regulators used to spend their time and energy scrutinizing the cement industry to detect any signs of collusion between the key operators of what had already been an oligopoly for many years. But in today’s global scale economy, European regulators have become less shy about allowing the formation of giant companies capable of capturing sizable shares of the market in major European countries; after all, Europe needs a few such global heavy-weights to avoid being completely dwarfed by Asia and the Americas.

Just over a decade ago, uniting Holcim and Lafarge would have been unthinkable. Regulators used to spend their time and energy scrutinizing the cement industry to detect any signs of collusion between the key operators of what had already been an oligopoly for many years. But in today’s global scale economy, European regulators have become less shy about allowing the formation of giant companies capable of capturing sizable shares of the market in major European countries; after all, Europe needs a few such global heavy-weights to avoid being completely dwarfed by Asia and the Americas. Whereas the course of events in Europe has followed a well predicted roadmap, the unpleasant surprise on the path to Holcim and Lafarge’s union has now come from India where the regulators fear that the Holcim – Lafarge deal would cause a serious imbalance on their very vast and growing market. In an interesting and quite unusual move, India’s CCI (Competition Commission of India) required Holcim and Lafarge to publish the details of their proposed deal on their respective websites as well as in a selection of national newspapers, so that every interested party in the Indian subcontinent could have access to the relevant information and be given sufficient time to formulate comments and possible objections. This is only the second time that a merger proposal is submitted to general public scrutiny under Section 29(3) of India’s Competition Act, 2002.

Whereas the course of events in Europe has followed a well predicted roadmap, the unpleasant surprise on the path to Holcim and Lafarge’s union has now come from India where the regulators fear that the Holcim – Lafarge deal would cause a serious imbalance on their very vast and growing market. In an interesting and quite unusual move, India’s CCI (Competition Commission of India) required Holcim and Lafarge to publish the details of their proposed deal on their respective websites as well as in a selection of national newspapers, so that every interested party in the Indian subcontinent could have access to the relevant information and be given sufficient time to formulate comments and possible objections. This is only the second time that a merger proposal is submitted to general public scrutiny under Section 29(3) of India’s Competition Act, 2002.

Cement is bulky, heavy and of low value relative to its weight. The market catchment area for any given production plant is therefore quite limited as transport costs rapidly outweigh economies of scale. The positive side of this is that cement is one sector in which mature economies are not likely to be invaded by Chinese production, even if China now accounts for more than half of the world’s cement consumption. A producer’s geographical spread is therefore a key factor. In that sense, Holcim and Lafarge complement each other particularly well in the fast growing economies, as the former is strong in Latin America and Asia whilst the latter is well positioned in Africa and the Middle East. The pair believe that the lower risk and business fluctuations resulting from better geographical spread will reduce their borrowing costs, thereby generating annual savings of some 200 million Euros.

Cement is bulky, heavy and of low value relative to its weight. The market catchment area for any given production plant is therefore quite limited as transport costs rapidly outweigh economies of scale. The positive side of this is that cement is one sector in which mature economies are not likely to be invaded by Chinese production, even if China now accounts for more than half of the world’s cement consumption. A producer’s geographical spread is therefore a key factor. In that sense, Holcim and Lafarge complement each other particularly well in the fast growing economies, as the former is strong in Latin America and Asia whilst the latter is well positioned in Africa and the Middle East. The pair believe that the lower risk and business fluctuations resulting from better geographical spread will reduce their borrowing costs, thereby generating annual savings of some 200 million Euros. Conceptually and intellectually, this is quite an appealing and exciting challenge, but it is difficult to imagine such transformation within the next three to five years in two companies which until now have relied mostly on size and hegemony (and some times price-fixing when the going became too tough) rather than being agile and capable of re-inventing themselves by adding a service veneer over their heavy industry core.

Conceptually and intellectually, this is quite an appealing and exciting challenge, but it is difficult to imagine such transformation within the next three to five years in two companies which until now have relied mostly on size and hegemony (and some times price-fixing when the going became too tough) rather than being agile and capable of re-inventing themselves by adding a service veneer over their heavy industry core.